Ye hallow'd bells, whose voices thro' the air / The awful summons of affliction bear: / Ye slowly-waving banners of the dead

November 2: Soulmas (Fire | Soulmas Tables | Soul Bells)

YE hallow'd bells, whose voices thro' the air

The awful summons of affliction bear:

Ye slowly-waving banners of the dead,

That o'er yon altar your dark horrours spread:

Ye curtain'd lamps, whose mitigated ray

Casts round the fane, a pale, reluctant day:

Ye walls, ye shrines, by melancholy drest,

Well do ye suit the fashion of my breast!

Have I not lost what language can't unfold,

The form of valour cast in beauty's mould!

Th' intrepid youth the path of battle tried,

And foremost in the hour of peril died.Edward Jerningham, Honoria: or the day of All Souls, a poem, with other poetical pieces (1737-1812)

Soulmas (also known as All Souls’ Day, the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed) is the conclusion to Hallowtide - a wintry denouement that extends our attention to our dead and to our landscape, interrupting our comfortable routines with calls toward prayer.

We have records of monasteries commemorating their dead as early as the 9th century, and Masses had been said for the dead long before then. St. Odilo (the French Benedictine abbot of Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France) formalized this commemoration of the dead in 998 AD, organizing a day of song, prayer, & almsgiving attached to the day after Hallowmas.

These prayers and traditions gravitated toward an idea that would eventually form the basis of the doctrine of Purgatory, a theological concept that had been debated about for centuries and wasn’t officially recognized by the Western Church until 1274; shortly thereafter, in the 14th century, All Souls’ Day was additionally recognized by Rome. Purgatory (from the Late Latin pergatorium, a ‘place of cleansing’) encompassed the belief that the souls of the dead - the Church Penitent - could be helped and affected by the prayers of the living. Though Purgatory came to be visualized as a place, it was intended to describe a process.

I realize this can get into difficult territory for many; just as Purgatory had been wrestled about for centuries, Christians continue to wrestle with it1 across denominations. Historically, we can look to examples like the English Reformation, where we see Soulmas traditions being removed - but still finding their way back into popular celebration over time.2

Wherever we land on the spectrum of belief about the afterlife, there seems to be an almost intrinsic impulse to set aside opportunities to remember our dead and to realign ourselves within the context of the larger cloud of witnesses.

“In the toil and moil of life we too easily forget the dead, or remember them only with a sense of loss instead of gratitude. Hence it seems well that once in the year an opportunity should be afforded for dwelling on them in a different way, for recalling all that endeared them to us, which often means all that has lent our past life its emotional value…”

William Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities (1897)

Agrarian communities - tied as they were to the cycles of growth & decay on their land, as well as to a reliance on their family, neighbors, & heritage - found ways of marking Soulmas that were profoundly simple & tangible.

Let’s look at a few rural customs that used to close out Hallowtide commemorations - and might still have something to surprise us or offer us.

For more on Hallowtide:

Refiner’s Fire

Illuminating the darkness is a hallmark of Hallowtide. Whether in the form of carved Jack-o-Lanterns or kale torches, candles are lit as beacons in the night to help guide us through the transition to winter and to remind us of our common journey beyond the veil of this life.

As we reach Soulmas in this triduum, though, the familiar flame suggests still more depth of meaning - transformation, refinement, movement, purification.3 Agrarian communities lit bonfires and torches throughout Hallowtide, but this tradition became especially meaningful in commemorating Soulmas; in focusing attention on their departed loved ones, they pondered not just their ancestors’ momentous crossover from life to death, but also grappled with the mysterious question of the journey partaken after death. The movement of the soul, shed of mortal life, toward God: an unknowable process of transformation.

The Soulmas torches lit in these rural spaces were called Tinleys - a word often varied in its spelling, it seems to have been derived from the Old English tendan (to kindle) or Old Irish tenlach (a hearth):

“…fire [is] an emblem of immortality typifying the ascent of the soul into heaven. In some parts of the kingdom, [Catholics] were wont to illuminate their grounds by bearing round them straw, etc, kindled into a blaze. This ceremony is called a Tinley and was performed on the Eve of All Souls, emblematical of the lighting of souls out of purgatory.”

G. F. Nothall, English Folk-Rhymes (1892), referencing Gent's Magazine (1788)

These tinleys were visual reminders of the soul’s upward yearning4 toward God. Whatever one’s stance on the doctrine of Purgatory5 (either among our ancestors or ourselves), those Soulmas fires visualized the unknowable, refining movement of the soul into God’s presence - and even after being suppressed, tinleys found a way to be enjoyed ecumenically. Soulmas fires remind us that our compassion for our dead is not limited by the veil of death.

A practical element of the lighting of tinleys helped to further embody their symbolic meaning - farmers would encircle their fields at Soulmas with lit tinleys, a tradition meant to deter noxious weeds6 while also serving as a visual reminder to pray for our dead and our land.

In this, we see people praying for God’s blessing upon the souls and soil that have shaped their own lives.

“Heath, broom, and dressings of flax, are tied upon a pole. This faggot is then kindled. One takes it upon his shoulders; and, running, bears it round the village. A crowd attend. When the first faggot is burnt out, a second is bound to the pole, and kindled in the same manner as before.”

William Hone, The Every-Day Book

Rethinking the Table

“On the second day of this Month, on which is commemorated The Feast of All Souls, it hath been a Custom, time out of mind, for good People to set on a Table-Board a high heap of Soul-Cakes, lying one upon another, like to the Shew-Bread in the Bible.

“They were in form about the bigness of a Two-Penny Cake: And every Visitant took one of them. And, there is an Old Rhyme, or Saying, which alludes to this, viz.

“ ‘A Soul-Cake!

A Soul-Cake!

Have mercy on all Christen Souls, for

A Soul-Cake!’ ”“This Pious Custom, (for such it is) is still in use in some Parts of Cheshire, Lancashire, etc. And, were it, together with sundry other Innocent Ones, revived in all Places, we should have more true RELIGION, and less FRAUD and ENVY in the World.”

John Aubrey, Shropshire, ca. 1686

We’ve previously chatted about the tradition of souling during Hallowtide, when soulers would go door-to-door, trading their songs & prayers for a soul cake, fruit, or other form of alms.

The prayers of this neighborly custom extended not only to the wellbeing of the dead, though, but also to the wellbeing of the land and the livestock:

“Among many other customs may be noticed, that of baking large cakes called Soul Mass Cakes, which were given to the poor on this day; and in return for which the latter used to pronounce benedictions on certain crops; and couple it with good wishes for the soul of the donor:

“‘God save your soul

Beans and all’”Thomas Forster, ed., The Perennial Calendar and Companion to the Almanack (1824)

However mischievous or rowdy the traditions surrounding souling became over time, inherent in them is a kernel of attentiveness…a profound belief in our attachment across time and circumstance to the unseen: to God, to the souls of our dead and our neighbors, and to the land that shapes us. We’re asked to re-examine the boundaries and limitations of our limited scope & perspective.

The eve before Soulmas would also see the setting of a table for the dead, whether with soul cakes or other delights; a space was set aside as a stark, physical reminder of the eternality of our lost loved ones.

“Before they went to sleep, however, the children had to prepare for the coming of the dead. They spread a table with a clean white cloth and placed an uncut loaf on it. Water was set there, too, in case a poor soul were parched and thirsty.”

Florence Berger, Cooking for Christ: Your Kitchen Prayerbook

If you’ve experienced the loss of a loved one, I’m sure you can relate to me here - that overwhelming sense of missing them at the table. Inspired by this Soulmas table tradition, I’ve found it extra meaningful to pull recipes from my family - Grandma’s sugar cookies, I’m looking at you - and make those for Soulmas. Studying their flourished cursive and recreating a meal they loved feels a bit like bridging the gap in a tangible way. We’re not pretending that we’re having dinner together as we used to, but acknowledging and intentionally honoring our eternal connection to them.

If you don’t have old family recipes to draw from to enjoy at your Soulmas table, consider looking for recipes that hail from your ancestors’ hometowns or places of heritage - a practice that bears the connection to both a person and a place.

If you’re looking for some help with Soul Cakes, I have two recipes - one historic, one modern - available here!

Soul Bells

As Passing Bells7 were historically rung to mark the death (or impending death) of a community member, Soulmas came to adopt the ringing of these bells whole-sail - rung throughout Hallowtide, but especially prevalent on Soulmas, these bells called the faithful to remember and to pray.8 It was a holy interruption; a bell toll asking people to pause in their full lives and recall their dead.

“The following simile expresses well the heavy knell of large Soul Bells:

“‘Night Jars and Ravens, with wide stretched throats

From Yews and Hollies9 send their baleful notes -

The ominous Raven with a dismal chear

Through his hoarse beak of following horror tells,

Begetting strange imaginary fear,

With heavy echos like to Passing Bells.’”Thomas Forster, ed., The Perennial Calendar and Companion to the Almanack (1824)

Though church bells aren’t ringing throughout Soulmas anymore, we might consider how we can interrupt our own busy lives to remember the dead on this day; maybe setting an alarm on our (often omnipresent) phones, surprising us every few hours with the call to prayer?

We also like a simple Soulmas garland - just plain twine hung with bells and photos of our lost loved ones.

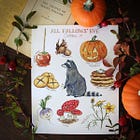

Art + Resources

For quick references for Hallowtide & some family activities, hop into the Scriptorium

More art is available in my Etsy shop!

“On All Souls’ Day the living pray for the dead, affirming the unity of souls from one end of time to the other.”

Laurence Whistler, The English Festivals

The afterlife is the great mystery that can quickly preoccupy us beyond the point of being fruitful, so as always, let’s enter these questions with our senses alert and accept our limitations. We aren’t meant to know the mechanics of mystery; and whatever we believe about the afterlife or our prayers for the dead, I can’t help but believe that praying for the dead certainly changes us - the living, here and now. It’s a humbling practice that can help to realign our vision of how we fit into the world by placing us within the context of our ancestral people and places.

Memento mori, friends! Wishing you and yours a blessed Hallowtide.

Pax vobis,

Kristin

If you’d like to make a one-time donation, I have a PayPal Tip Jar - please know that I’m so grateful for your monetary support, which really does help me continue to do this work that I’m so passionate about!

For those who are able to support a monthly or annual paid subscription, I offer occasional new printables, extra posts, and access to my whole library of printables: the Scriptorium. I’m so grateful for your generosity, which helps to support my work through the purchase of additional books for research, art supplies, and more!

For more reflections and perspectives on the liturgical year, please visit Signs + Seasons: a liturgical living guild!

Whether wrestling with the named doctrine of Purgatory, or wrestling with the question of an intermediate state of the soul after death.

“Once people were thwarted in their attempts to bring comfort to the dead within churches, they developed different strategies to provide prayers in a ritual framework outside them” (Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun).

“And I will put this third into the fire, and refine them as one refines silver, and test them as gold is tested. They will call upon my name, and I will answer them. I will say, ‘They are my people’; and they will say, ‘The Lord is my God.’” (Zecariah 13:9 ESV)

I’m borrowing a title here from a beloved book: The Soul's Upward Yearning: Clues to Our Transcendent Nature from Experience and Reason by Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ

This became a significant issue with the English reformation, as various historic traditions were tested; some traditions, even though they fell out of favor for a time, found their way back into use and were like common ground later.

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun

“Bourne considers the custom of the Passing Bell as old as the use of bells themselves in Christian churches about the seventh century. Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, speaking of the death of the Abbess of St. Kilda, tells us, that one of the sisters of a distant monastery, as she was sleeping, thought she heard the wellknown sound of that bell which called them to prayers, when any of them had departed this life. Bourne thinks the custom originated in the religious idea of the prevalency of prayers for the dead. The Abbess of the monastery above alluded to had no sooner heard the bell, than she raised all the sisters and called them into the church, where she exhorted them to pray fervently and sing a requiem for the soul of their mother.” ( Thomas Forster, ed., The Perennial Calendar and Companion to the Almanack (1824))

“…the peals rang out from the moment that the liturgy ended until midnight, and so it probably was in the parishes. […] In this way the opening of the season of darkness and cold had been made into an opportunity to confront the greatest fear known to humans, that of death…” (Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun)

Liturgical plant-lore emergency! Holly and yew both symbolized the Passion of Christ, and yew in particular suggested themes of resurrection. Fitting botanicals to host this raven of the passing bell on Soulmas.

I think as we get older this day takes on deeper and deeper yearning and curiosity about the other side. In our culture even horror movies distance themselves from the dead. We just don’t want to believe one day our turn will come. I read a book recently about a Catholic priest who helps “caught” souls get to the other side. They were for whatever reason hesitant to move on. Don’t know what to make of it exactly but it was really interesting.

So, so good, Kristin. This Evangelical-with-no-ties-to-liturgy is grateful for a glimpse of the origins and meanings behind many long lost and forgotten practices. Oh, that they would return!

In the meantime, your notes abou the triduum of Hallowmas will have to do as a small place (however virtual) of recalibration and encouragement. Thank you!